Golden Fleece 1550 Shipwreck Gold Bar Clip (14.24 grams)

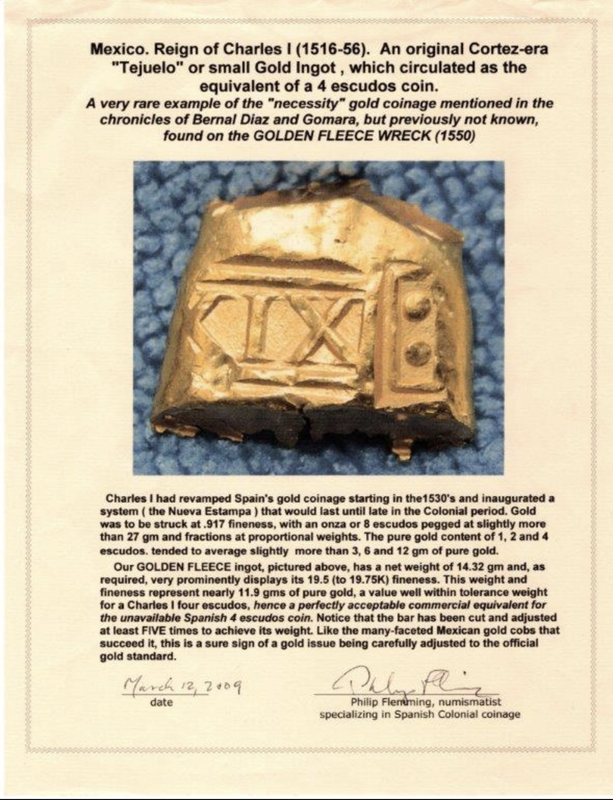

Mexico Reign of Charles I (1516-56). An original Cortez-Era “Tejuelo” or small Gold Ingot, which circulated as the equivalent of a 4 escudos coin. A very rare example of the “necessity” gold coinage mentioned in the chronicles of Bernal Diaz and Gomara, but previously not known, found on the GOLDEN FLEECE SHIPWRECK (1550)! (Weight 14.24 grams)

Charles I had revamped Spain’s gold coinage starting in the 1530’s and inaugurated a system (the Nueva Estampa) that would last until late in the Colonial period. Gold was to be struck at .917 fineness, with an onza or 8 escudos pegged at slightly more than 27 grams and fractions at proportional weights. The pure gold content of 1.2. and 4 escudos tended to average slightly more than 3, 6 and 12 grams of pure gold.

Our GOLDEN FLEECE ingot, listed here, has a net weight of 14.32 grams and, as required, very prominently displays its 19.5 (to 19.75k) fineness. This weight and fineness represent nearly 11.9 grams of pure gold, a value well within tolerance weight for the Charles I four escudos, hence a perfectly acceptable commercial equivalent for the unavailable Spanish 4 Escudos coin. Notice that the bar has been cut and adjusted at least FIVE times to achieve its weight. Like the many-faceted Mexican gold cobs that succeed it, this is a sure sign of a gold issue being carefully adjusted to the official gold standard.

The “Golden Fleece Shipwreck 1550” Northern Caribbean Sea

The accompanying artifact is a genuine ingot recovered from an unidentified shipwreck sunk circa 1550 in international waters in the northern Caribbean Sea. This unidentified wreck is noteworthy for its yield of small, round, flat silver patties, or “splashes,” as well as gold bars and pieces of bars that were probably used as early gold coins during the joint reign of Joanna (the Insane) and her son Charles I of Spain (1516-55). Many of the silver “splashes” bear a stamp that shows the letter C (for Charles) below a crown (the “Crowned-C” mark). Inn addition some of the gold bars and pieces bear a stamp that shows a castle between two pillars with the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece hanging below the castle. This stamp is also linked with Charles I, who was credited with reviving the medieval Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in the early 1500s. (The collar of the Golden Fleece also appears prominently on later, milled gold coins of Spain in the 1700’s.) The gold bars from this 1550 shipwreck present the first evidence ever seen of the “Golden Fleece” marking on bullion from the New World.

Even the ingots without the “Golden Fleece” mark are among the most important material to enter the market in many years. Since no gold coins were made in the Spanish colonies until the 1680s, the necessity for tradeable amount of gold was alleviated by cutting into pieces the long, thing gold bars known as “finger bars,” which were stamped several times along their lengths to allow the stamps to be visible on each cut piece. The stamps typically represented only two things: The fineness, marked in Roman Numerals as parts per 24 (like the modern-day karat), and the royal tax seal, showing that the “King’s Fifth” had been paid. The silver bullion was similarly marked but was not cut down like the gold, as silver coins were abundant. Although, apparently not as early as the mixed-metal “tumbaga” bars found on a wreck in the Bahamas in 1992, the small silver “splashes” from this wreck were created by simply pouring the melted silver into a round depression, as opposed to the huge, rectangular wood-mold ingots from later sources like the Atocha, which sank in 1622 off Key West, Florida.

The approximate date of this wreck is determined by the following facts: (1) The “Crowned-C” and ‘Golden Fleece” marks indicate production during the reign of Charles I, which ended in 1556, when he abdicated the throne in favor of his son, Philip II; (2) many of the ingots resemble those found from the 1554 Fleet, sunk off padre Island, Teas; but also (3) other markings appear to slightly pre-date the 1554 Fleet, although not as early as the “tumbaga” bars of the late 1520s. Therefore the ship in question most likely sank in the 1540s or early 1550s. Unit more evidence is found (like a ship’s bell or cannon, which typically bore dates and places of manufacture, if not the name of the ship itself), this wreck must simply be considered one of the Spanish homebound ships lost in the mid-16th century, which were almost too numerous to count.

Charles I had revamped Spain’s gold coinage starting in the 1530’s and inaugurated a system (the Nueva Estampa) that would last until late in the Colonial period. Gold was to be struck at .917 fineness, with an onza or 8 escudos pegged at slightly more than 27 grams and fractions at proportional weights. The pure gold content of 1.2. and 4 escudos tended to average slightly more than 3, 6 and 12 grams of pure gold.

Our GOLDEN FLEECE ingot, listed here, has a net weight of 14.32 grams and, as required, very prominently displays its 19.5 (to 19.75k) fineness. This weight and fineness represent nearly 11.9 grams of pure gold, a value well within tolerance weight for the Charles I four escudos, hence a perfectly acceptable commercial equivalent for the unavailable Spanish 4 Escudos coin. Notice that the bar has been cut and adjusted at least FIVE times to achieve its weight. Like the many-faceted Mexican gold cobs that succeed it, this is a sure sign of a gold issue being carefully adjusted to the official gold standard.

The “Golden Fleece Shipwreck 1550” Northern Caribbean Sea

The accompanying artifact is a genuine ingot recovered from an unidentified shipwreck sunk circa 1550 in international waters in the northern Caribbean Sea. This unidentified wreck is noteworthy for its yield of small, round, flat silver patties, or “splashes,” as well as gold bars and pieces of bars that were probably used as early gold coins during the joint reign of Joanna (the Insane) and her son Charles I of Spain (1516-55). Many of the silver “splashes” bear a stamp that shows the letter C (for Charles) below a crown (the “Crowned-C” mark). Inn addition some of the gold bars and pieces bear a stamp that shows a castle between two pillars with the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece hanging below the castle. This stamp is also linked with Charles I, who was credited with reviving the medieval Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in the early 1500s. (The collar of the Golden Fleece also appears prominently on later, milled gold coins of Spain in the 1700’s.) The gold bars from this 1550 shipwreck present the first evidence ever seen of the “Golden Fleece” marking on bullion from the New World.

Even the ingots without the “Golden Fleece” mark are among the most important material to enter the market in many years. Since no gold coins were made in the Spanish colonies until the 1680s, the necessity for tradeable amount of gold was alleviated by cutting into pieces the long, thing gold bars known as “finger bars,” which were stamped several times along their lengths to allow the stamps to be visible on each cut piece. The stamps typically represented only two things: The fineness, marked in Roman Numerals as parts per 24 (like the modern-day karat), and the royal tax seal, showing that the “King’s Fifth” had been paid. The silver bullion was similarly marked but was not cut down like the gold, as silver coins were abundant. Although, apparently not as early as the mixed-metal “tumbaga” bars found on a wreck in the Bahamas in 1992, the small silver “splashes” from this wreck were created by simply pouring the melted silver into a round depression, as opposed to the huge, rectangular wood-mold ingots from later sources like the Atocha, which sank in 1622 off Key West, Florida.

The approximate date of this wreck is determined by the following facts: (1) The “Crowned-C” and ‘Golden Fleece” marks indicate production during the reign of Charles I, which ended in 1556, when he abdicated the throne in favor of his son, Philip II; (2) many of the ingots resemble those found from the 1554 Fleet, sunk off padre Island, Teas; but also (3) other markings appear to slightly pre-date the 1554 Fleet, although not as early as the “tumbaga” bars of the late 1520s. Therefore the ship in question most likely sank in the 1540s or early 1550s. Unit more evidence is found (like a ship’s bell or cannon, which typically bore dates and places of manufacture, if not the name of the ship itself), this wreck must simply be considered one of the Spanish homebound ships lost in the mid-16th century, which were almost too numerous to count.